Unconventional and Unafraid: How Christian Jollie Smith Dared to be Different

Trinity CollegeOn 20 March 1918, a pleasant autumn morning, ‘Pamela Brown’ took to the roads for the first time. Only a few short months before a global pandemic would have a devastating impact on Australia, the sight of a young woman at the wheel of her own car was still novel. Even more curious was one setting herself up as Melbourne’s first female taxi driver. A Herald article observed:

‘Miss Brown is a charming girl, tall and slight, and wears orthodox chauffeur’s uniform at the wheel, although this week, she has been trying the traffic of Melbourne streets in unofficial dress. She has qualified at the City School of Motoring, does her own running repairs, and can mend a car on the road.’

The young driver offered the Herald journalist an explanation for her unconventional career path, saying she ‘was tired of all the interesting things happening outside my windows – of seeing the world from the windows of a business office. I wanted to become acquainted with the wind and the weather again.’

At the time, there was much happening outside Pamela’s windows. Australian poet “Nettie” Palmer, a close friend from their time together at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, would confide the secret identity of the entrepreneurial chauffeur in her diary – Pamela Brown was Christian Jollie Smith (TC 1906). At the time, Christian was in a relationship with Scottish-born William Earsman, a labour movement activist, whose wife was well advanced in her pregnancy with the couple’s daughter. Earsman himself was being tracked by the Commonwealth security service because of his far-left leanings. Christian would be caught up in the same web.

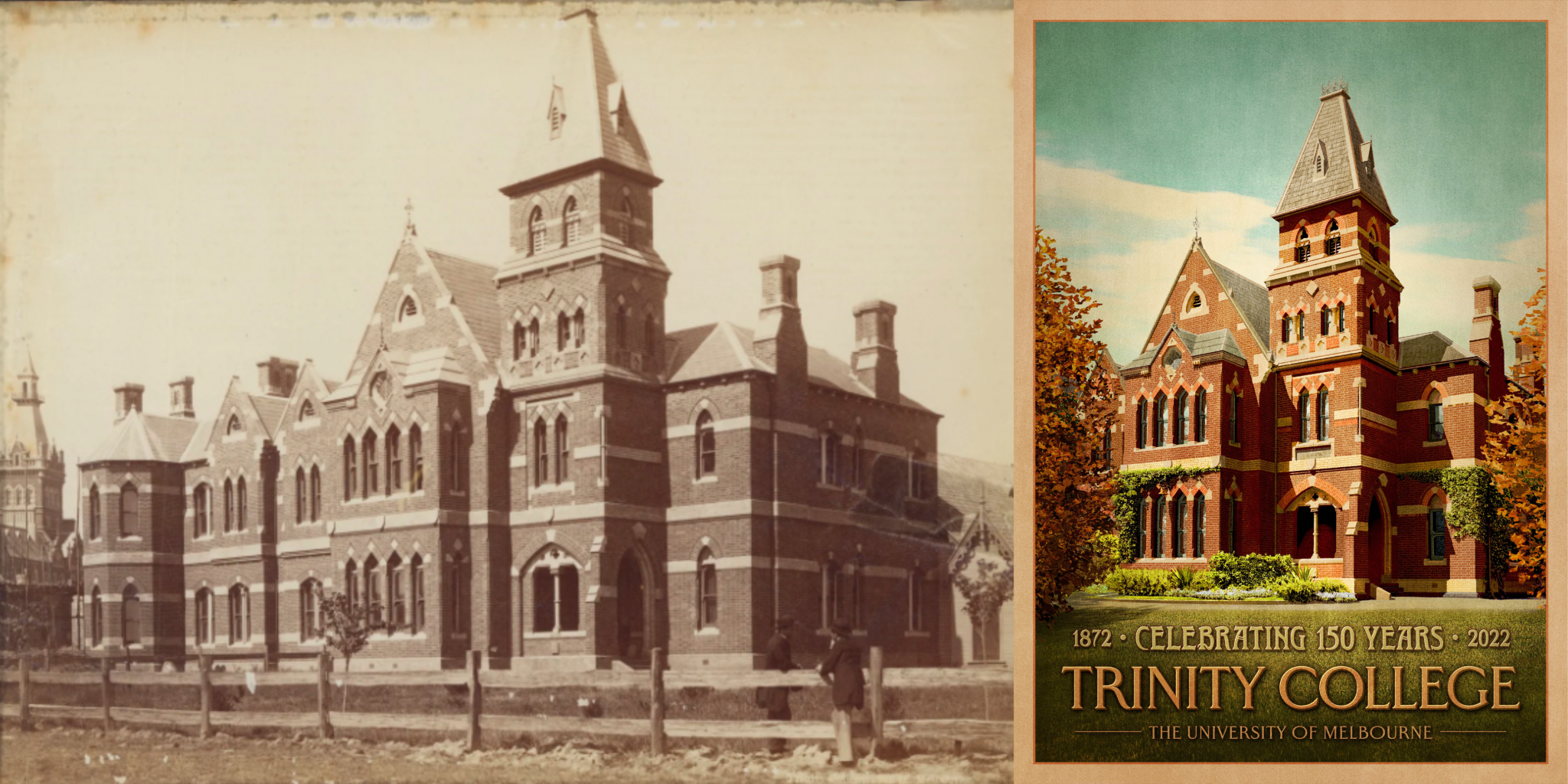

Christian Brynhild Ochiltree Jollie Smith was born on 15 March 1885 to Thomas Jollie Smith, a talented academic and theologian, and his wife Jessie Ochiltree McLennan. Thomas enrolled at the University of Melbourne in 1877, commencing at Trinity College in 1880, the year he won the College Dialectic Society’s President’s Medal for Oratory. Engaged as a tutor and then lecturer at Trinity between 1880 and 1890, Thomas had completed his BA and MA degrees, graduating with first-class honours in language and logic, by the time Christian was born.

In 1886, when Trinity’s Women’s Hostel was established on Trinity Terrace on the west side of Sydney Road (now Royal Parade), Thomas took up the position of the hostel’s inaugural principal. Thomas, Jessie and young Christian lived in one of the terrace houses; the female students (six in 1886 and four in 1887), who paid 50 guineas a year for their board, lived next door.

Christian followed her father into Trinity, commencing at the Women’s Hostel in 1906 while studying at the University. She had an early interest in the Classics, securing second-class honours in deductive logic and history the next year, before realigning her academic pursuits.

Engineering held Christian’s focus but the challenges for a woman were, she felt, insurmountable. Medicine or law seemed the practical avenues in which women had already forged a path at the University. On the toss of a coin, she enrolled in the latter and graduated with a Bachelor of Laws in 1911.

In October the following year, she became the third woman admitted to the Victorian bar as a barrister and solicitor, after fellow University of Melbourne graduate Flos Greig had shattered that ceiling in 1905; a barrier broken only through the introduction of Victoria’s Women’s Disabilities Removal Act of 1903 enabling women to become legal practitioners. All the same, the ambiguity of her ‘striking quartette of baptismal names’ meant that, in admitting her to the bar, the Supreme Court judge mistakenly announced the new admission as ‘Mr Smith’, before quickly apologising.

In 1914, on the eve of the First World War, Christian set up her practice at Stallbridge Chambers in Melbourne’s Chancery Lane. Though she was initially supportive of the war, the 1916 conscription debate and her earlier friendships forged at Trinity with socialist-leaning alumni such as Guido Barrachi (TC 1906), whose anti-war sentiments had resulted in him being thrown into the University lake in 1917, saw Christian reverse her position. Interviewed in 1975, Barrachi suggested that:

She may have started on her way to the Left by being feminist-minded, but at the time I met her she was already more absorbed in things like the Labor College and then the communist movement. And the feminism would remain.

Her growing involvement in socialist circles was undoubtedly part of the ‘interesting things happening outside’ her windows as she gazed out into the streets from the Crown Solicitor’s Office where she was employed as a professional assistant for several months in late 1917. Files of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch (CIB) within the attorney-general’s department reveal it was during her time there that she first came to their attention. Following an inquiry into ‘the leakage of certain information’ concerning the planned deportation of social activist Adele Pankhurst, daughter of the famed British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, Christian’s employment with the Crown Solicitor’s Office abruptly concluded.

It was in the months that followed, she set herself up as a taxi driver before difficulties with the chauffeurs’ union – which, ironically, considered her an ‘upstart capitalist’ – brought this short-lived venture to a close.

She supported herself by teaching English literature at Melbourne High School and Brighton Grammar throughout 1919, the same year she published The Japanese Labor Movement and, collaboratively with Nettie Palmer, produced the commemorative collection of writings titled The War on the Workers, in memory of the socialist writer Leon Villiers, who had died in April 1918, aged 44.

Moving to Sydney in 1920, Christian continued teaching English literature at the Labor College of New South Wales. It was here, in the Harbour City, that Australian intelligence reports would record that ‘her extremist tendency appears to have reached its full development’.

On 30 October, she was one of a group of 26 – including three women – who gathered at the Australian Socialist Party Hall in Liverpool Street for the founding meeting of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA).

When the party’s manifesto was published a few months later, it became clear

that Christian had not only attended the meeting; she was one of the eight signatories to the document. Moreover, as the CIB recorded, she ‘was stated to be the proprietor and publisher of the Australian Communist, the official organ of the Communist Party.’

Christian remained in Sydney where, in 1924, she became only the second woman solicitor to be admitted in New South Wales.

‘I would never have gone back to Law were it not for the Labor Movement,’ she told The Labor Daily, explaining her return to practice. She practised law for the following four decades, often in the areas of industrial law and workers’ rights.

As the CPA grew rapidly throughout the 1920s and 1930s, she successfully fought two attempts by then attorney-general (later Sir) Robert Menzies to have the party declared illegal in Australia. The second of these included advising Dr HV Evatt, during his time as leader of the Australian Labor Party, during the anti-Communist referendum in 1951. A few years later in 1954, when the defection of two Soviet diplomats captured national attention as the ‘Petrov Affair’, Christian acted as solicitor for Australian diplomat Ric Throssell, accused by Vladimir Petrov of having leaked to Moscow information on the couple’s defection.

—–

When Christian died in North Sydney on 14 January 1963, the city’s Tribune newspaper, to which she had long been a contributor, honoured her by noting that her death ‘takes from the Australian working class movement one of its most devoted fighters in the intellectual and professional fields.’

A friend, a counsellor, and a valiant national champion for human rights, world peace and a better life for the working masses, Miss Jollie Smith will live on in the thoughts of many and in the history of the Australian working-class movement.

Banner image: Christian Jollie Smith, on the left, leaving the Royal Commission on Espionage, 13 April 1954. National Archives of Australia.