A Journey through “The art of healing”

Henry Forman Atkinson Dental Museum & Medical History MuseumThese works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists (on public display in the foyers of major buildings and student spaces) inform visitors of First Nations traditions and healing practices. Please take the time to visit these locations and experience the cultural knowledge and aesthetic power embodied in these works.

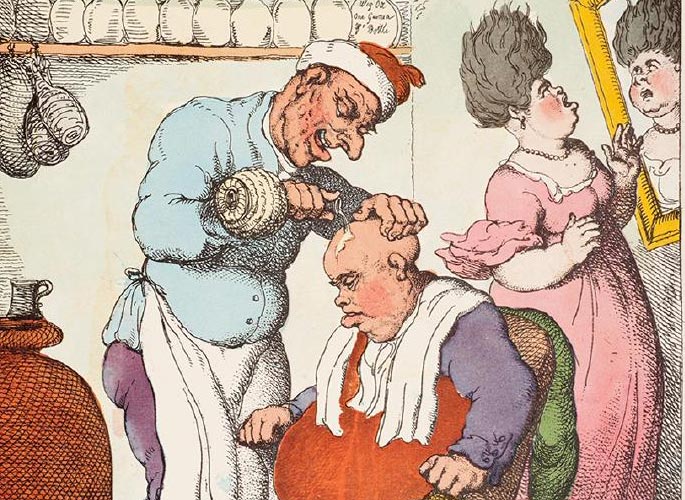

Treahna Hamm (b. 1965),

language: Yorta Yorta

Country: Yorta Yorta

artist location: Yarrawonga, Victoria

Dhungala cool burn, 2017

acrylic paint, river sand, bark ink, paper on canvas100.9 × 114.0 cm (each of three panels)

MHM2017.2, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

Bush medicine and knowledge have been connected to what is known as ‘cool burns’ in many parts of traditional Aboriginal homelands, usually practised during the autumn months. Low-intensity fire was and is done to manage and maintain plant, tree and grass growth. It regenerates and brings into being new growth, buds and shoots, continuing the cultural process of gathering food and medical resources. This process was part of a vast knowledge that is held between the sky, land, people and wildlife, all connected within lore and story to people and land. Cool burns were also practised to clear built-up areas of bushland, so that hunting and gathering would be easier, and foods and bush medicines more clearly recognised in the environment.

The triptych depicts traditional times of Yorta Yorta women and girls collecting bush foods and remedies, with their dilly-bags hung from their shoulders—after cool burning occurs. The figures stand in honour of ancestral knowledge along the bank of dhungala (the Murray River), which is symbolised by the hands of ancestors holding billabong sediment. This also contains the symbolism of healing, along with the continued benefits of medicinal knowledge, hand in hand with spirituality in more than 2000 generations of people on Country. The oval shapes in the foreground are coolamons; inside them are seeds, pods and reeds that have been gathered before the cool burning took place. The coolamons have been painted with local river-bark ink. Its use is vastly versatile, as the bark ink is also used in the creation of medicine in Yorta Yorta Country.

Cassie Leatham

language: Taungurung / Wurundjeri of the Kulin Nation

place of birth: Gunai Kurnai country,

Country: Taungurung / Wurundjeri of the Kulin Nation

artist location: Boisdale, Gippsland

Healing Mat , 2019

native grasses, emu feathers and feather flowers

MHM2020.21, Medical History Museum

Cassie has created this Healing Mat from locally sourced native grasses, emu feathers and feather flowers. The piece contains 3000 bunches of emu feathers, which adorn the edge of the healing mat.

Cassie Leatham is from the Taungurung / Wurundjeri of the Kulin Nation. Cassie’s biological grandfather George Patterson Fisher was a Taungurung man and Cassie’s biological grandmother Alice Biddy Stevens was a Wurundjeri and Gunai Kurnai woman. Cassie’s father Ron was adopted at a young age to Georges sister Jean and her husband Jack Leatham. Ron grew up knowing his biological parents as his Unc and Aunt, as did Cassie but knew there was a stronger connection. Cassie was born in Sale on Gunai Kurnai country and takes pride and place in the local community and has been a member at Ramahyuck in Sale, Gippsland and is also a member of her Taungurung country.

Cassie knew her connection to her country was strong and once her heritage was confirmed, a sad time when her biological grandfather passed. She was 15 years old. Cassie started exploring her heritage and looking to elders to help her with her journey and belonging. Many assisted and she continued her journey embracing culture, teaching her knowledge and skills in art and traditional methods used by her ancestors. Cassie has worked in many schools all over the country and continues to this day mentoring Koorie youth in culture and identity.

Cassie facilitates workshops in a variety of media and specialises in native indigenous bush plants. It’s nurturing culture and heritage and respecting the land, the elders, the traditional ways that are most important to Cassie and most importantly nurturing the aboriginal youth who will one day become elders and become the teachers for generations to come. Cassie resides at Boisdale in Gippsland.

Copyright for both the artwork and text remains with Baluk Arts and the artist.

Rosie Ngwarraye Ross (b. 1951)

skin: Ngwarraye

language: Alyawarre

Country: Ampilatwatja

artist location: Ampilatwatja, Northern Territory

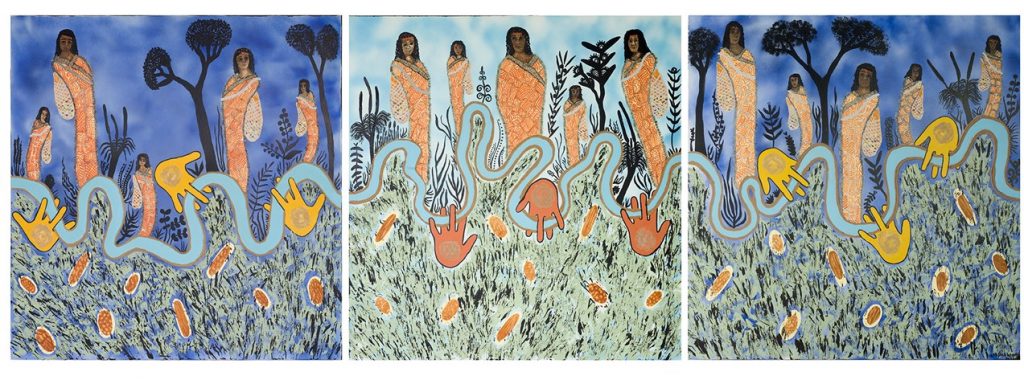

Bush flowers and bush medicine plants, 2015

acrylic on linen

91.0 × 91.0 cm

MHM2017.3, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

Rosie Ross loves to paint, and she is constantly inspired by Country. When she goes hunting, she enjoys seeing the bush flowers and looking for bush medicine:

‘We look for these plants in rocky country, we can find a little purple plum that we use to clean the kidneys and sometimes for flu. The yellow flowers are used for scabies; we boil them and add water and wash our skin with it. The pink flowers we use for when we have sore eyes; we mix the flowers with water and the colour changes to a light green. Communicating this love, knowledge and appreciation of Country and all it provides is important to Rosie, because ‘it keeps culture strong’. Communicating this love, knowledge and appreciation of Country and all it provides is important to Rosie, because ‘it keeps culture strong’.

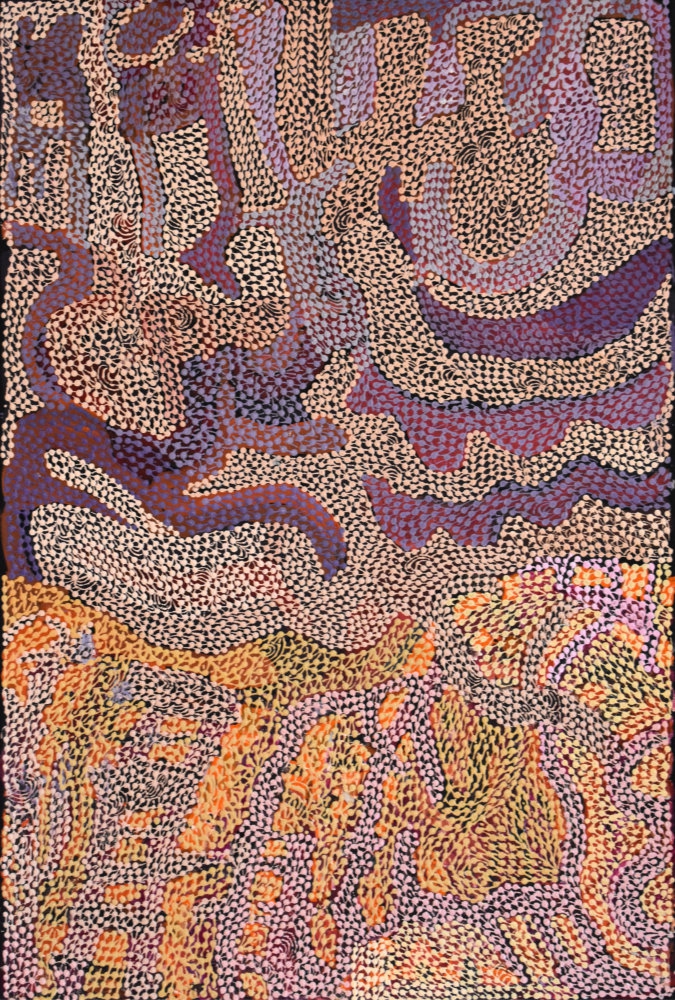

Marie Mudgedell

Bush Baby Story, 2020

acrylic on canvas

90 x 60 cm

MHM2021.9 , Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

Marie has depicted a birthing story from the past. The right way for a baby to be born is this way. Birth was sacred. The mother and the women with the right skin – … would go away from the main camp. They would make a windbreak for the mother and for the baby to be born. No man was allowed anywhere near where the baby was being born. The men went away from the main camp too. They went hunting for food. The other women, with the wrong skin names for that new baby, would stay somewhere in the middle, not in the main camp, not with the birthing camp. They would look after the other children, and also go hunting for bush food. When the baby was born, then the father might be able to see that new one.

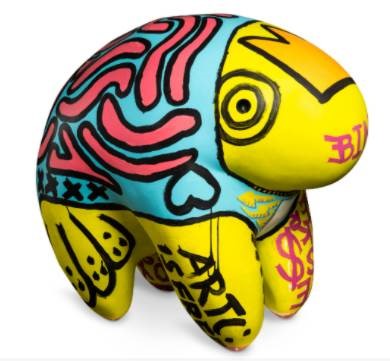

Josh Muir ( b.1991)

Language Yorta Yorta/ Gunditjmara

Binga 2020

fibreglass, paint

MHM2021.7

Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

Binga by Josh Muir is a named after a word that comes from his son’s own unique lingo. It means balloon. This UooUoo is inspired by Josh’s son’s imagination. “His reaction was epic; I feel I hit the mark within a child’s mind.”

Josh Muir is a Melbourne-based multi-media artist who presents a new narrative and movement in contemporary Indigenous Australian art. Muir uses digital prints and video art to communicate voices of dissent and create dialogue from the artist’s own perspective. He recalls his origin story as a graffiti artist working in Ballarat, drawing from his Yorta Yorta, Gunditjmara, Dja Dja wurrung, Wada wurrung and Barkindji ancestry. The language of Indigenous visual culture is expressed through vibrantly coloured digital prints that pays homage to the dynamic tradition of street art and hip-hop.

“I am a proud Yorta Yorta/ Gunditjmara man, I hold my culture strong to my heart and it gives me a voice and great sense of my identity. I look around I see empires built on aboriginal land, I cannot physically change or shift this, though I can make the most of my culture in a contemporary setting and my art projects reflect my journey.” – Josh Muir.

Mary Katatjuku Pan (b. 1944)

language: Pitjantjatjara

community/location: Amata, Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, South Australia mother’s Country: Kunytjanu

father’s Country: near/south of Wataru

artist location: Ingkerreke Outstation, Rocket Bore, Northern Territory

Tjulpu wiltja wala waru Tjukurpa: eagle nest story basket, 2017

tjanpi, wool, raffia, emu feathers, wire

80.0 × 30.0 cm (diameter)

MHM2018.31, Medical History Museum

‘This is the story about the wedge-tailed eagle. This is my big sister’s and my Tjukurpa. The wedge-tailed eagle soars a long way up in the air and can see everything. He can see all the food from up above, and all the living things are frightened of him. He cares for his little eaglets. He gives them food, proper bush tucker.

We feel the same way about our family and care for them, too. We hunt for goanna, witchetty grubs, fruits and berries from our land, feeding our kids to live a healthy life. The wedge-tailed eagle, when he gets tired, he rests in his nest. He takes care of his family in his nest and looks after them very well. We also take good care of all our family.’

Mary Katatjuku Pan (translation by Margaret Smith, with kind assistance from Tjala Arts and Lilian Wilton)

Tjanpi (meaning ‘grass’) sculptures evolved from a series of basket-weaving workshops held on remote communities in the Western Desert by the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council in 1995. Tjanpi sculptures were first produced in 1998, when Kantjupayi Benson, from Papulankutja, added a handle to a basket and made a grass pannikin (metal cup) followed by a set of camp crockery and a number of dogs. Aṉangu women of the Central and Western Desert have, for a very long time, worked with natural fibres to create items such as bush sandals (wipiya tjina), pouches (yakutja), hair-string skirts (mawulyarri) and head-rings (manguri) for daily and ceremonial use. Adding a contemporary spin to the traditional, women now create baskets, vessels and an astonishing array of vibrant sculptures from locally collected desert grasses, bound with string.

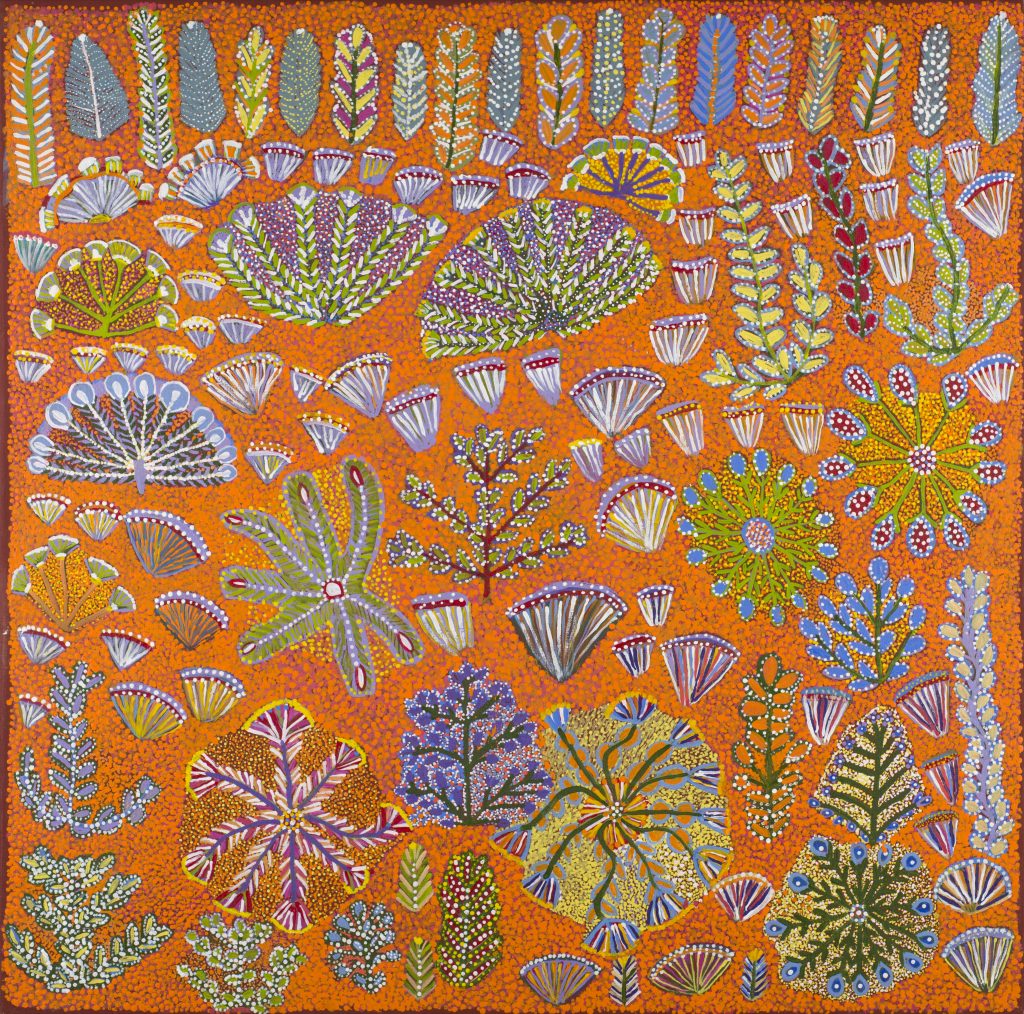

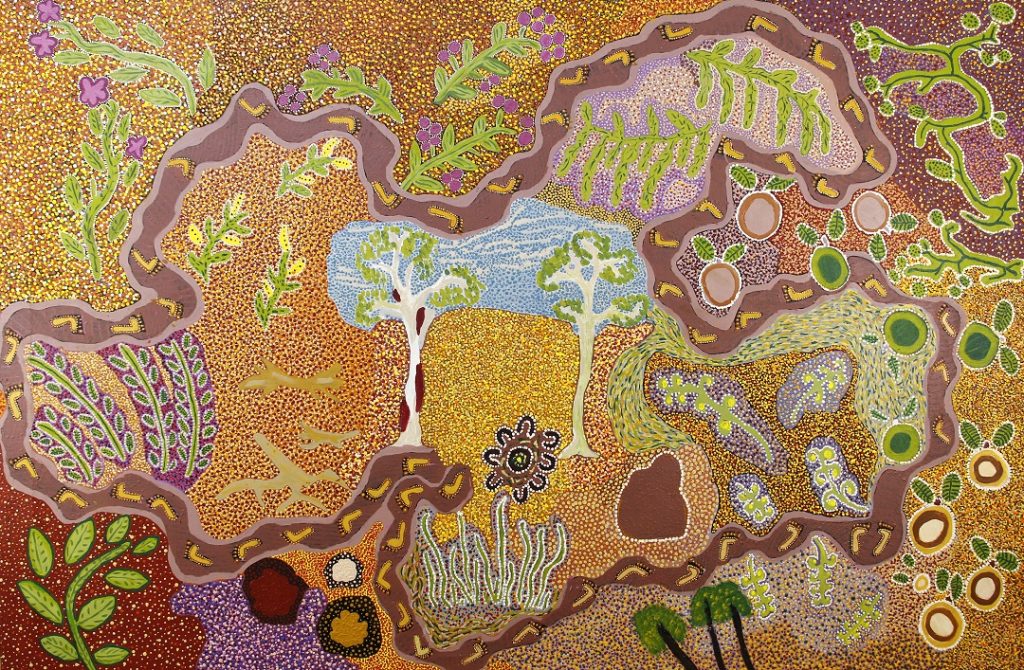

Balgo artists: Miriam Baadjo, Tossie Baadjo, Jane Gimme, Gracie Mosquito, Helen Nagomara, Ann Frances Nowee and Imelda Yukenbarri

Miriam Baadjo (b. 1957)

skin: Nangala

language: Kukatja

Country: Tjatjati

Tossie Baadjo (b. 1958)

skin: Nangala

language: Kukatja

father’s Country: Nyilla grandmother’s Country: Karntawarra

Jane Gimme (b. 1958)

skin: Nungarrayi

language: Kukatja

Country: Kunawaritji

Gracie Mosquito (b. 1955)

skin: Nangala

language: Walmajarri / Kukatja Country: Puruku

Ann Frances Nowee (b. 1964)

skin: Nungarrayi

language: Kukatja

Country: Nyilla

Imelda Yukenbarri (b. 1954)

skin: Nakamarra

language: Kukatja

Country: Winpurpurla

Helen Nagomara (b. 1953)

skin: Napurulla

Country: Kulkurta

artists location: Wirrimanu (Balgo), Western Australia

Bush medicine: a collaborative work by women from Wirrimanu (Balgo) , 2018

acrylic on linen

120.0 × 180.0 cm

MHM2018.32, Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

In the centre of the painting are two trees; on the left is the Wirrimangulu or Bloodwood tree. The sap from the tree is a powerful medicine, boiled in water until melted, and drunk for any serious ailment, including cancer tumors. Tinjirl or Mulan Tree (River Gum) grows by the riverside. It has powerful cultural significance and forms part of the seven sisters Tjukurpa for the region. It is used for law and for smoking ceremony to cleanse bad spirits. It can also be inhaled for respiratory problems.

The central trees are surrounded by a variety of plants, leaves, fruits, barks, roots and other bush medicines. The pink flowers on the top left of the painting represent the Karnpirr-Karnpirr plant. The shiny, fat leaves are crushed and mixed with animal fat to make a Vicks-type rub to treat children’s colds. To the right are the Pampilyi (Bush Kiwi). The seeds are used to make tea for kidney cleanse. Top centre is the Marnukitji (Conkerberry). The berries are high in antioxidant and vitamin C and the roots are ground and used to make a rub for pain relief—and have a very good smell. Centre right is the Tjipari (Eucalyptus) leaf for smoking newborn babies. In the right-hand corner is the Warrakatji (Bush Vine) that is wrapped around the forehead for relief of migraine. Down the right side of the painting is the Tjukurru (Bush Passionfruit), which are boiled along with the leaf of the plant and drunk as a medicinal tea for stomach ailment. To the left of these fruits is the Piriwa (Grevillea) for sweet water. The bark is ground and applied to the skin for treating ringworm and sunburn. Underneath the two central trees is the Ngapurlu-Ngapurlu. Milk from this grass is used for sores, but can also be used for permanent hair removal. To the left of the grasses is piltji (red ochre), used for spiritual healing and ceremony. Above the ochre are the roots and parntapi (bark), which are ground, boiled and drunk for stomach pain. Bark can also be applied to hair to promote hair growth.2

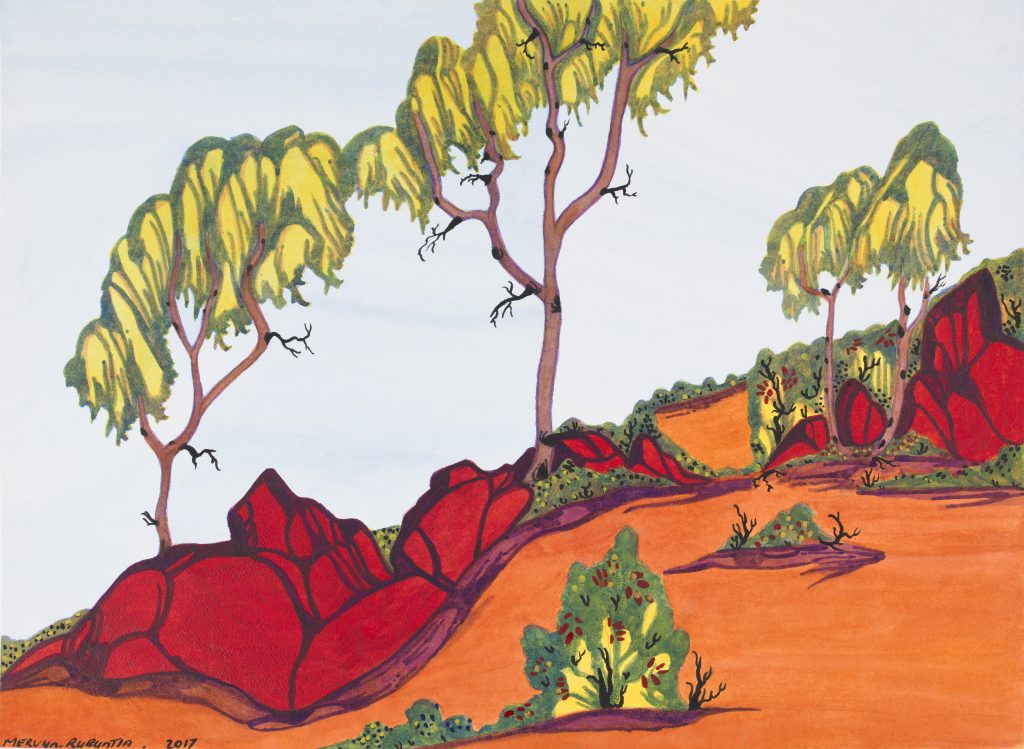

Mervyn Rubuntja (b. 1958)

skin: Japanangka

language: Arrernte

Country: Maduthara from father’s side, Ntaria (Hermannsburg) from mother’s side

artist location: Mparntwe (Alice Springs), Northern Territory

Bush medicine in Jay Creek, NT, 2017

watercolour

54.0 × 74.0 cm

MHM2018.11, Medical History Museum

I choose to paint the area of Jay Creek. It is a traditional Western Arrarnta land, because it has all the traditional plants, bush medicine and bush tucker. There is an old lady, I call her aunty, the older sister of Dolcy Sharp. Both sisters’ homeland is in Jay Creek. This area is rich with bush medicine. She often collects some bush medicine and brings it to town (Mparntwe) to show and to gift to other family members. My sister-in-law gets those leaves and chops them and boils in water.

Back in the day people didn’t have a car, they had to walk long distances. That is how they discovered the different assets and attributes of the plants. Warlpiri and Anmatyerre people used to walk to Mparntwe (Alice Springs) to have ceremony.

Bush Berries are used as bush medicine and go through a different process. Some of the Elders used to buy large containers and collect the berries. They would leave them in the sun for a while to dry, and then boil them. They would then drain them. The berries they would then use as a rub to treat diverse skin conditions such as sunburn. The liquids from the cooked berries are tipped into a bottle. This is being drunk to treat stomach conditions. In the past people suffered less from rashes and skin conditions due to those bush medicines. In the painting, the red berries—they turn orange, you can consume them in both states.

Urrarlpa (Native Tomatoes) are found in hilly, rocky habitats. People smell or chew the leaves and it aids in cleansing the body. Some of the black dots are Black Berries—chew good for young and old. Other black dots are Kupaarta (Bush Plum). The gum trees are Lupa-ipenha thungarlpa (gum from Elegant Acacia). People grind this gum and then suck it. People drink young boiled gum tree leaves, or they suck it. They use this often when alcohol-poisoned. I used to do this too. Inmurta (Mustard Grass) grows sometimes attached to other native plans. During wet weather they grow together.

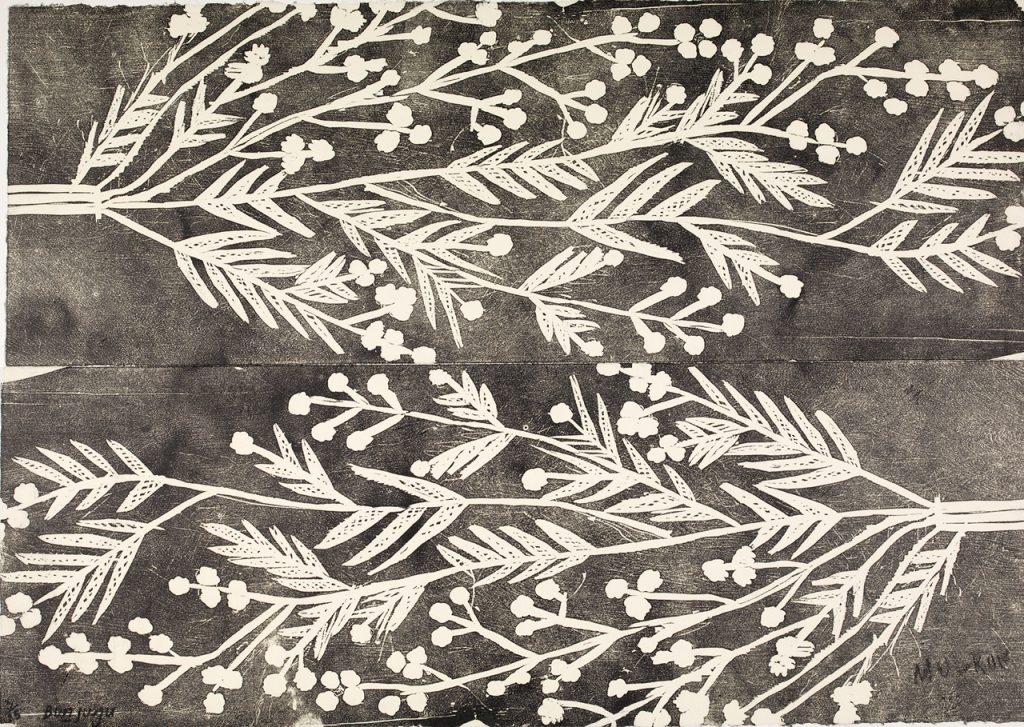

Mulkun Wirrpanda (1946-2021)

language: Dhudi-Djapu

clan: Dhudi-Djapu / Dha-malamirr moiety: Dhuwa

artist location: Yirrkala, Northern Territory

Buṉdjuṉu, 2014

woodblock, edition 3/25

81.0 × 57.0 cm

MHM2017.39, Medical History Museum

This is an image of a bush plant named Capparis umbonata, which is the only Australian member of the family that includes capers. It is also known as Bush Orange, Wild Orange, or Buṉdjuŋu. It is common at Yathiikpa near Yilpara, where sometimes I live. I have developed an interest in promoting plants that are no longer eaten widely. As a child I remember there were very many old people and that now there are so few. I blame the poor diet and the loss of knowledge of this and other such plants. You pick the fruit and then leave it for three to four days to ripen—it is red on the inside. You peel it like an orange.

Bark with a few leaves added can be boiled in water to make a medicinal wash to cure sores of the skin, scabies and boils. The roots can also be boiled in water and the liquid used as a wash to provide relief from painful joints such as knees and hips. The fruit is considered good food, eaten raw when ripe.